A Close Reading of RM Haines

Lyricism and Brutality

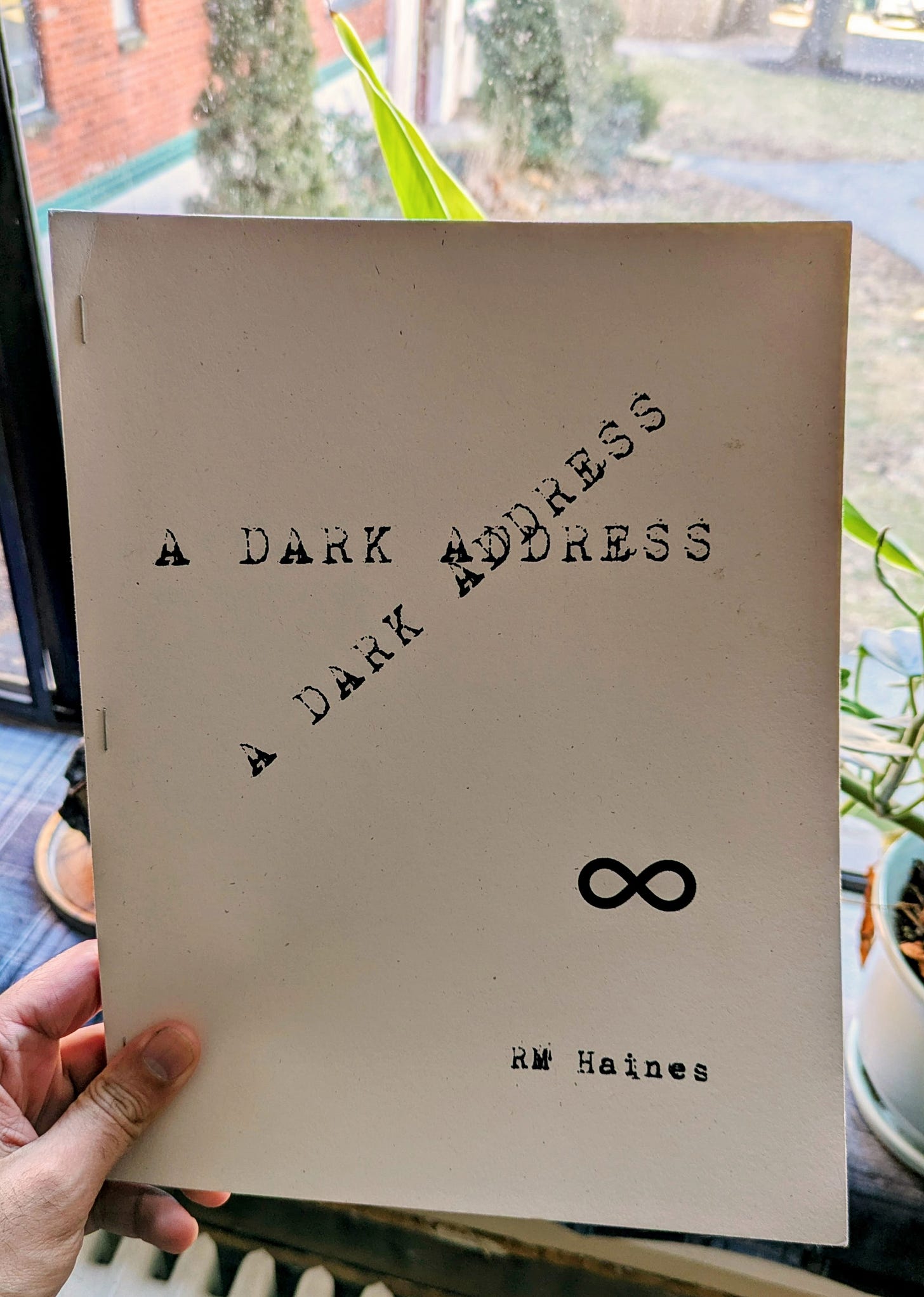

I began reading RM Haines’ A Dark Address sometime in 2020. I loved the book for its mysterious lyricism and set out to write about Haines’ particular lyric mode. In the ensuing years, I opened and closed the work intermittently, jotting down impressions and thoughts with the intent of collapsing them into a singular essay, and as I was doing so a great many things happened in the world: a pandemic, an election, the re-establishment of American neoliberal blitheness, and the release of Interrogation Days, Haines’ chapbook. The style in Interrogation Days is sharp, fractured, stark, and in many ways the opposite of the style in A Dark Address—or at least this is what I thought on my first read. As I spent more time with the difficult poems in Interrogation Days, the difference in style between the two works became less a chasm and more a bridge. In this essay I discuss the architecture of that bridge.

“A Story about the Liver,” my favorite poem from A Dark Address, builds in its first stanza a voice of Lucretian calm and resoluteness:

Evenness is its virtue.

Organ of wood, of roots,

it tempers the sped blood,

mothering and toning its richness.

In one tradition, it belongs

to spring, to budding forces

fusing what’s buried deep

to all that branches, flowers,

and falls free. Daily,

its work turns through cycles

timed to the sun’s changes,

and in sleep, it begins to cleanse,

releasing dross and poison.

A close reading of this opening stanza reveals the voice’s preoccupation with action and motion: the “organ of wood” tempers the quick blood, and mothers its richness; it “belongs to spring,” but spring is immediately qualified by the season’s workings, forces which bud and fuse: branchings, flowerings, and fallings. The voice then moves from the seasonal to the daily workings of the changing sun, which in turn leads us, through the circadian activity of the body, to the defining function of the poem’s ostensible subject, the liver: to purify and to release the speeding blood.

The voice, then, is itself in motion; it pours from the heights of generality into the narrow body—not simply a generic body, but the specific body of this speaker saying in the next stanza:

For those full of ills,

this troubles dreams.

Old crimes kept buried

rise and branch jaggedly,

and each twisted limb

mars your lover’s face.

But who is the speaker, and what to him is the liver? What is an organ? What is the body? The poem raises these questions by having the speaker introduce a rift between an agent and their activities. Let’s revisit the first stanza: the liver there, this “organ of wood, of roots,” is almost platonic: there’s no mention of the body within which the organ must work. “Blood” appears in the second line, but the mode of the stanza refracts its material into a lambent but generalized Idea-of-Blood. We have then, in the first stanza, Liverness: the work that an organ can theoretically do, must do, and which gives it its being. But as we’ve seen, what powers the voice is its rush from broad to narrow, from universal to individual, from liverness to this liver, this organ found in this fearful self where cleansing has slowed, and the “dross and poison” reach face-height. When the function of an organ stops, what makes it still be that organ?

The liver cannot answer. “Fear,” says the punning speaker, “belongs to the liver”:

It chases you into anything

You aren’t, just to hide.

[…]

Free of interiors, of organs

and secrets—it is immune,

sheltered among the weeds.

The stanza is striking because of these two absurdities that deepen questions of identity and usher the poem to its climax: the organ is a part, and its definition as such always locates it in a body; a shelter can’t be a shelter without interiority (metaphorical or otherwise). And yet the liver, while continuing to be an organ, is free of organs, and all the while hiding in interiority, it’s free of interiors. Generalizing these two statements clarifies the contradiction: X continues to be X while fleeing things constituting X.

What makes the poem so potent is not simply the derivation of an anomaly in logic but also its exploration of the life deep within that anomaly. The remainder of the poem exudes a profound and simple poignancy. In the “weeds,” what was once an organ becomes stone:

A small boy finds its place.

In his shallow pocket,

he carries the stone home

where he washes it in rosewater

and bores a hole through its core

to let the air pass through.

Washing the stone is an act of deep, careful, and Rilkean compassion. The boy bores a hole and creates a space; into it pours the world, and into the world are dissolved those distinctions troubling the previous stanza—universal vs particular, organ vs body and so on. And the liver, functioning or not, is once more made part of the larger body. The poem ends with a complicated, grief-ridden acceptance as unflinching as its compassion: “Once, you were my body,” the speaker says, addressing not simply the organ, but the boy and the organ—this act of speech, like a mantra, awakens the speaker completely to himself. No part of him, at this moment, can be hidden: “The sun can read. / The air is your own mind.”

“A Story About the Liver” ends by opening into a dappled kind of freedom enmeshed within its own lyricality. When the lyric mode appears in Haines’ 2023 chapbook, Interrogation Days, it does so grotesquely and on the verge of satire. These newer poems are brutal. They pull lines from CIA documents and torture reports; they quote Dick Cheney, Rumsfeld, and Obama; they willfully purge themselves of rosewaters and tenderness.

The first poem of Interrogation Days is simply titled “Drone,” and brings to bear, in the two opening stanzas, the various glosses on the titular word: a musical drone, the drone of a voice, the drone bee. The camera drone that rises out of the third section is the drone that permeates the rest of the collection:

The drone glides its way outward.

Its eye scans a world of forms,

their texture, wavelength, radiance.

It goes wherever. There are no

borders for a drone. Attuned,

piloted by a strange intelligence,

it knows which sites to light upon—

the softest targets to pursue.

Here is the capitalist counterpart of Rilke’s angels, those paradigms of the lyrical. In the first of the Duino Elegies, Rilke writes, “Angels (they say) don’t know whether it is the living they are moving among, or the dead.” Here, drones survey without much fuss the industry that, just as coldly, gave them life. Both the angel and the drone exist in a realm of differencelessness—but Rilke’s mystic angel (like the speaker of “Liver,” at the close) is one with all of being; to the drone all being, all that is perceived, is nothing but one possibility: that of the drone’s “soft target.” So the machine hovers like fate above that unitary field, and the task of identifying life, death, the task of sparing life, bringing death, falls to the minds outside the drone. These minds then must speak the language of the drone, language that the poems replicate within themselves: “When you know everything about someone, you can do anything to them,” writes Haines, and “What I’m going to do to you is going to be fucking disgusting.”

The titular poem in Interrogation Days has one tongue in the drone idiom, the other in the angelic; the consequences wrought thereby are startling. The first two sections of the work are brutal, not simply detailing Abu Gharib’s tortures but also the underlying strategy behind them. The strategy is drone-making, hinging on moving “soul” from the metaphysical to the epistemic realm: “Two doctors paid by the CIA / knew enough of the soul’s needs / to reverse engineer its collapse.” The soul is a thing to be known; it is abstracted into a postulate and its vertices and minute curves recorded. Then things are done to it; it accordingly swells, shrinks, stretches, gasps. When it presents itself at precisely the right angle, the observer hears “…the heart give birth / to raw, screaming thought-forms // flooding into imaginal space.” The observer logs the voice-giving angle. Then—he takes a copy of the Quran “…strung up with a used bra. / ‘You don’t really believe in // this shit, do you?’”

In the final section of the poem the lyric mode appears like an apparition with Haines’ invocation of The Speech of the Birds, an epic poem by the Sufi poet Farid ud-Din Attar:

In Attar’s epic, the pilgrim birds

Pledge obedience to the hoopoe,

a dream-bird, who guides them

through arduous valleys on the way

to the Simurgh, King of the Birds.

Attar’s The Speech of Birds is a poem steeped in wonder-struck mysticism. The birds in the poem plumb arduous valleys both allegorical and literal, and climb dizzying heights in quest for their king, the Simorgh, only to arrive finally back at the place where they started, the place which, they realize with wonder, they’d never left: they, they themselves, are the Simorgh, and have always been so, and will always be so. Attar’s poem begins to fold into “Interrogation Days,” and Haines continues:

In stress position, still sleepless,

one detainee began to talk. Valley

of the Quest. Valley of love. Valley

of mystery. Hallucinating dogs,

he watched them devour his family

and reported this to his interrogators.

In Attar’s poem, the birds returning to themselves is transcendent; they achieve unity. In Haines’ poem, the birds—the detainees, the tortured—return to themselves, become themselves—but the Simorgh here is the interrogator across yet another valley. For these “birds” the Simorgh has always been, and will always be the interrogator, the nation state. And a bird can only ever be a bird.

The lyrical voice in “Interrogation Days,” though, is not merely ironic. To be sure there’s biting irony in the voice, but even so Haines does not dismiss the lyrical even in the face of utmost cruelty—rather, the lyrical appears as a negative space among the gashes and gouges of war, capitalism, democracy, greed, cruelty. To put it more generally, Interrogation Days drops the lyric in the context of a nightmare world antagonistic to the lyric, and raises a bevy of difficult questions—what is the point of poetry? What can poetry do? And more, What is poetry? The danger of answering such questions is a temptation to veer into ideology which lifts itself above the shared world to define what is “real” once and for all time. In an interview, Haines says as much: “Ideology tells us the real is given, and we imagine within its borders, and we all learn to say ‘it is what it is.’ But it is not what it is: it is always full of contradictions.” In Interrogation Days, the lyric exists among ideologies taking as natural law the fiction of national identities, borders, nation-states, money, democracy, progress, warfare, selfhoods—the list goes on.

Among these “givens” poetry appears quaint. When the lyric is asked to perform the office of ideology, it appears absurd; when poetry is repurposed for the ends of ideology, it becomes an interrogator. In such a world, what is the use of poetry? Haines doesn’t answer; to answer the question would be to accept its insidious presuppositions. Rather Haines responds, and moves the lyric into a higher order of language: he makes a poem inside which the world does cruel things and asks nonsensical questions.